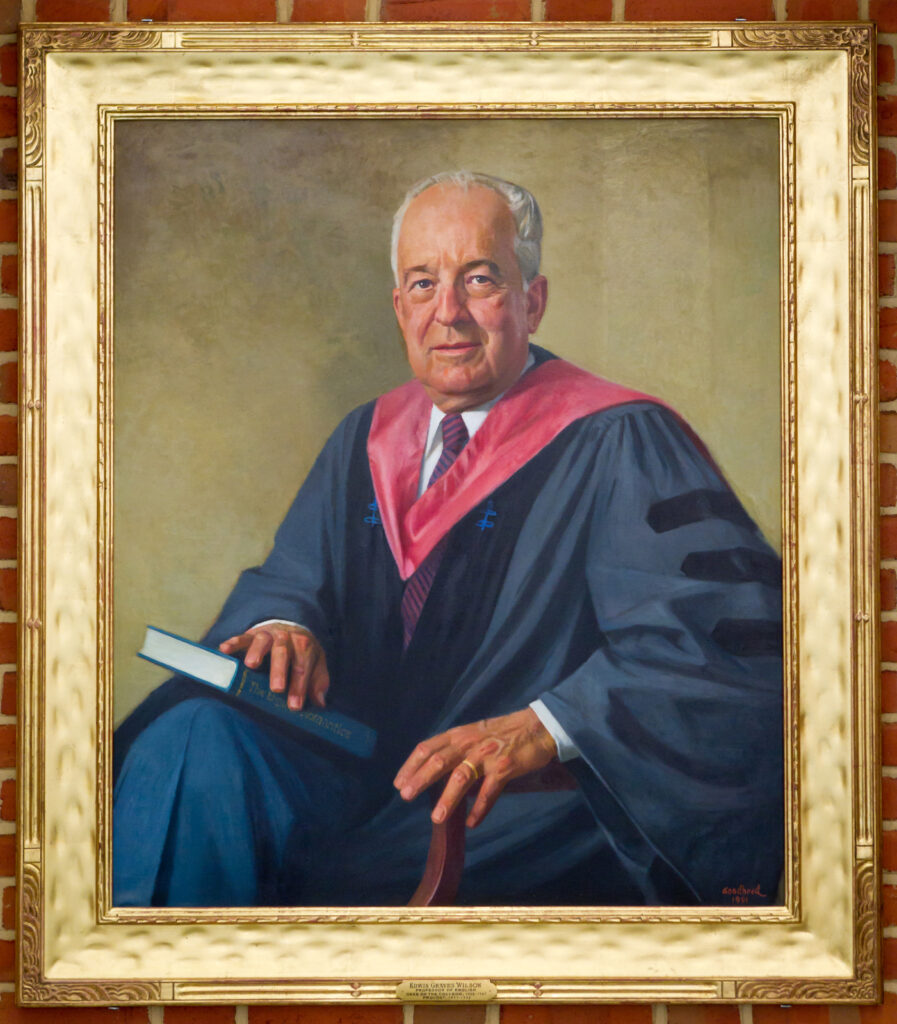

Ed Wilson’s Founders’ Day speech

“To Honor the Legacy,” 1992

Presented by Edwin Graves Wilson (’43)

at Founders’ Day Convocation,

February 6, 1992

Wait Chapel, Wake Forest University,

Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Audio

Listen to the speech on the Z. Smith Reynolds Library site

On a beautiful February morning in 1834, the sun shining and “balmy winds” blowing as if the month were May, a boy named John Crenshaw traveled, probably on foot, the three miles that separated his family’s country home from the Calvin Jones farmhouse in Wake County. At this farmhouse, it had been announced in North Carolina newspapers, the new “Wake Forest Institute” was being opened for the education of no more than fifty young men of at least twelve years of age and “of good character.” John Crenshaw was the first of sixteen students to register that February day under the watchful but benign guidance of the principal of the Institute, the Reverend Samuel Wait.

During the one hundred and fifty-eight years that have succeeded that modest “Founders’ Day,” thousands of young men – and, for the last fifty blessed years, thousands of young women – have followed John Crenshaw to the registration table and begun their Wake Forest years.

My own registration took place more than fifty-two years ago during the week that followed the beginning of the Second World War. I remember, without effort, the name and face of my adviser, the six courses that were listed on my registration card, some of the very words that were spoken at orientation, the walks by day and by night across the magnolia-covered campus and into the little nearby village, most of all the men and women who with patience, understanding, and love taught and counseled me. Some of those men and women are here this morning. I would like, with gratitude, to mention each of them by name, but I can do no more now than to salute them as a charmed circle of friends who gave me strength and hope for life. If Samuel Wait and John Crenshaw were the “founding” teacher and student, they – and others like them – were the defenders and preservers of those founding ideals that gave shape to what is best in the Wake Forest tradition.

For me – in 1939 – coming to Wake Forest, registering, and going to my first classes were, in the immortal words of Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca, the “start of a beautiful friendship.” Except for three years in the Navy and four years in graduate school, I have lived nowhere else, and the “beautiful friendship” has endured. I cannot pretend that every student, every teacher, every person working here has found at Wake Forest the “friendship” I have found. Some have instead experienced loss and disillusionment and, whether they have remained here or left, been deeply skeptical about Wake Forest’s proclaimed good intentions. Some of you in this Convocation audience may understandably dismiss my praise of Wake Forest as the natural, self-centered response of one student-teacher-administrator who is being especially honored today and who must therefore be thankful.

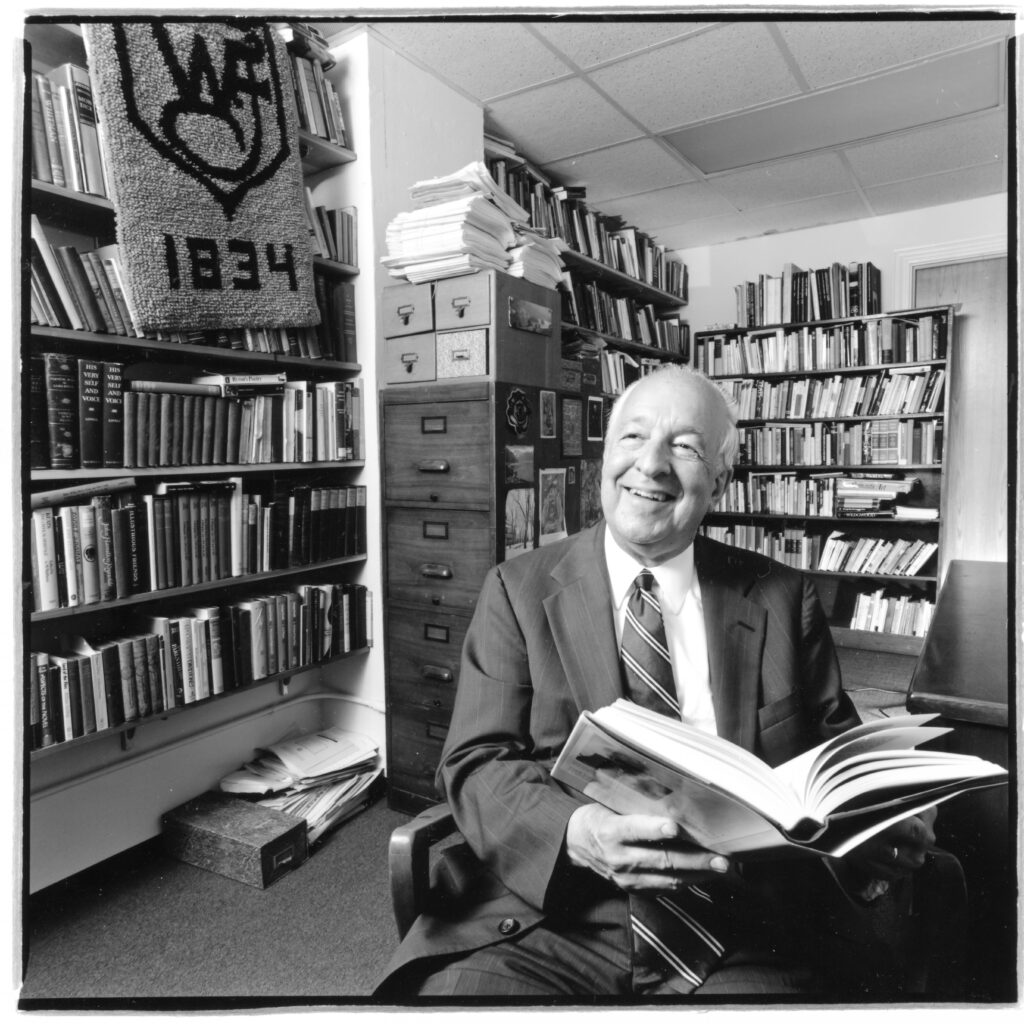

I will admit to being thankful. Thankful for more than forty-five happy years at Wake Forest. Thankful because it was on this campus, just a few minutes away from where I now stand, that I met the winsome and talented – and forthright – young woman who became my wife. Thankful because my much-loved three children were born and grew up here. Thankful because I learned at Wake Forest to embrace those certainties that John Keats proclaimed: “the holiness of the heart’s affections, and the truth of Imagination.” Thankful, especially, today to President Tom Hearn and to the Wake Forest Trustees for giving my name to one of the most creatively beautiful University buildings I have ever seen.

Thankful because that building is a library, and because books have been the intellectual center of my life, and because they are, for me, not only the center of the university but also, in Emily Dickinson’s words, the chariots that, more than any other instruments of our imagination, “bear the Human soul.” But my thankfulness today is not circumstantial. The events of this day, however heart-warming, are illustrative of what I have found at Wake Forest ever since my first registration day in September 1939.

Through the years, I have on occasion tried to identify the special character of Wake Forest: what it is that gives this college, this university, its own identity, unique among the institutions I have known. Today I recall, for insight into the nature of Wake Forest, the famous speech – incomparable in Wake Forest annals – made by President William Louis Poteat to the Baptist State Convention assembled here in Winston-Salem in December 1922. Under attack because of his defense of academic freedom at Wake Forest, he answered his critics with dignity and calm. He is perhaps best remembered for having said, “Welcome Truth… And do not stop to calculate the adjustment and revision her fresh coming will necessitate.” But he also said, “Our deepest need is to be good; after that, to be intelligent… What the world needs now as always is the… marriage of goodness and intelligence.”

Poteat’s word “intelligence” is the foundation of our modern academic vocabulary, and we applaud it without condition. Even those of our faculty members most rigorously trained in the methods of critical inquiry do not, I think, doubt that the end of our labors is the informed, the “intelligent” mind. We may differ about other accompanying values, but we elevate intelligence as the central article of our scholastic creed, as, in fact, do our colleagues in teaching and research at other colleges and universities across the land. We are still, in Emerson’s definition of the American scholar, Man – and Woman – Thinking.

But the genius of Wake Forest, I believe, has been created in the particular environment in which we have sought and transmitted intelligence and in which we have exalted man and woman “thinking.” From our “founding” we have been a place which has honored teaching – teaching defined not only through the familiar processes of lecture and seminar and laboratory but through those conversations between teachers and students, in and after hours, which bring to the developing mind illumination and insight and a new, unfolding awareness which is a kind of joy. I would hope that, on this Founders’ Day of 1992, we would renew our commitment to teachers and to teaching – nurtured, of course, by constant reading and reflection – and to the magical interplay between teachers and learners that invites trust and friendship. I hope also that we will reaffirm our belief in liberal education, never more needed than now, and in academic standards built upon the assumption of intense intellectual effort by the students and, from teachers, an evaluation of this effort which is fair and honorable ·and utterly worthy of respect.

William Louis Poteat’s other word in his 1922 speech, I remind you, was “goodness.” “What the world needs,” he said, is the “marriage of goodness and intelligence.” In the academic world of 1992 “goodness” is a word to be used with caution. To some among us, I am sure, it speaks of ancient and sectarian pieties acceptable enough to the North Carolina Baptist world of Presidents Wait and Poteat and “old” Wake Forest but no longer appropriate to the “modern,” well endowed, visibly successful Wake Forest of today and tomorrow. I might, more safely, find another word besides “goodness” to use. Loyalty? Compassion? Humanitarianism? Generosity? (“Generous” is a word I especially revere.) Love? But I will stay with “goodness” – even though some of my best friends on the faculty would wince if I should say to them that they are, in fact, “good.”

To interpret goodness as I understand it this Founders’ Day morning, let me turn now, not alone to our own history but rather to four voices from beyond Wake Forest who speak, it seems to me, with undiminished authority about that same “goodness” which President Poteat proclaimed. First, that gallant woman Eleanor Roosevelt, such a far-seeing pioneer for justice that, even thirty years after her death, she still seems to belong more to our future than to our past. She once said, in her own simple and unostentatious way, that “a person might not have much…to give, or to help other people with…But as long as you did the very best that you were able to do, then that was what you were put here to do….” When Eleanor Roosevelt died, a close friend of hers said, “while she was with us, no…[one] had to feel entirely alone.”

Next, that remarkable scientist statesman, Andrei Sakharov, who, in the darkness of Soviet totalitarianism, said, “ …there is a need to create ideals even when you can’t see any way to achieve them, because if there are no ideals then there can be no hope.” When Sakharov spoke those words in 1973, he probably did not, in fact, see a way, but his dedication to his ideals required such courage that, perhaps more than any other single person, he guaranteed the eventual birth of a new freedom for his people and his nation.

Next, that wise and compassionate survivor of the Holocaust, of Auschwitz and Buchenwald, Elie Wiesel, who, with so many reasons to despair, continues to insist that we must “testify.” We must, he says, “bear witness to what is, and to what is no longer.” We must “show the invisible world of yesterday and through it, perhaps on it, erect a moral world where just men are not victims and children never starve and never run in fear.”

And finally, a preacher who lived and died heroically and whose eloquence and passion still capture our deepest and most heartfelt emotions. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “One day we will learn that the heart can never be totally right if the head is totally wrong. Only through the bringing together of head and heart – intelligence and goodness – shall man rise to a fulfillment of his true nature.”

William Louis Poteat was president of Wake Forest University for twenty-two years. I chose Eleanor Roosevelt, Elie Wiesel, and Martin Luther King because of their innate virtues but also because each one of them once stood and spoke here – where I stand and speak this morning. Andrei Sakharov never visited Wake Forest, but we heard his voice from afar, and we listened.

I hope that my meaning is clear. If, as is certain, we can never return to that particular believing community over which Samuel Wait and William Louis Poteat once presided, we can create and maintain at Wake Forest a larger community which continues to remember Wait and Poteat and to proclaim their faith and to honor their legacy of unimpeachable character but also links them in brotherhood and sisterhood to Eleanor Roosevelt and Andrei Sakharov, to Elie Wiesel and Martin Luther King, to John Keats and Emily Dickinson, and to all those men and women whose ideals and powerful imagination we desperately need in an age when both intelligence and goodness seem to be so rare and so elusive. I like to think that, if Wait and Poteat were alive today, they would agree. Only with a vision which is thoroughly respectful of our North Carolina Baptist heritage and is yet universal in its nobility can we be certain that, as Wake Forest University grows in wealth, prestige, and success – as it, so to speak, “gains the whole world” – it will not “lose [its] own soul.”

I speak to you this Founders’ Day morning as a man of February. My own birthday was last Saturday – February 1 – and today, almost miraculously, is my father’s birthday. He was born in 1877, the same year in which William Louis Poteat was graduated from Wake Forest College. The first classes ever at Wake. Forest, as I have noted, were in February, not September. But from this month of winter came birth and life. And from this February celebration too, I hope, will come birth and life – not from me or from any of us who are in the winter of our lives. We must look rather, for intelligence and goodness, to those who are younger, especially to those of you who are still students and for whom, as once for me, this school was created.

In the last chapters of E. B. White’s children’s classic Charlotte’s Web, the spider Charlotte, having spun her last web, says to her friend Wilbur the pig, “Winter will pass, the days will lengthen, the ice will melt in the pasture pond. The song sparrow will return and sing, the frogs will awake, the warm wind will blow again. All these sights and sounds and smells will be yours to enjoy, Wilbur – this lovely world, these precious days…” And Charlotte continues: “You have been my friend. That in itself is a tremendous thing. I wove my webs for you because I liked you.”

I would conclude this morning by saying, with Charlotte, to all of you: my family, my colleagues, my students: “You have been my friend[s]. That in itself is a tremendous thing. I wove my webs for you because I liked you.”